Headlines

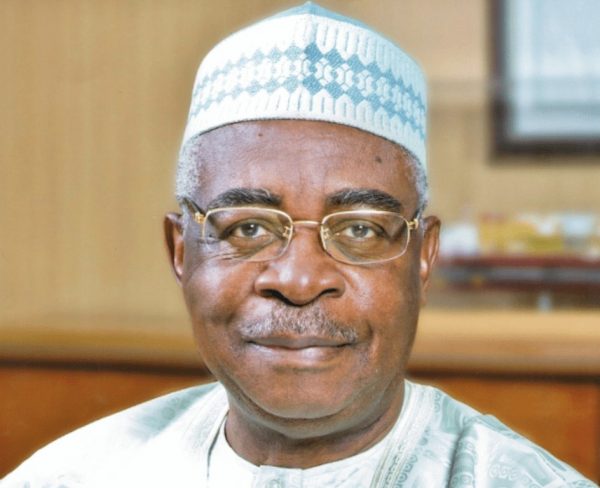

Gen TY Danjuma named in P&ID’s $9.6 billion judgment debt against Nigeria

- Says $40 million invested in gas project from him not P&ID

BY KAZIE UKO

Retired army chief, General Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma, has been named in the $9.6 billion Process and Industrial Developments (P&ID) Limited judgment debt currently rocking Nigeria.

Danjuma was said to be the brain behind the idea of setting up a plant that would convert wet gas to a form that it could be used for power generation.

The project was conceived to have the Federal Government of Nigeria deliver wet gas to P&ID, at no cost, while the company would in turn process the raw material and deliver back the refined gas to government, also at no cost, to use for power generation.

P&ID would instead profit from the by-products, butane and propane, that would be derived from the wet gas.

Had the project been carried through, the recalcitrant issue of gas flaring in the Niger Delta area would have become a thing of the past.

According to the authoritative Bloomberg Businessweek, Danjuma said the gas flaring project was originally his idea, and that one of his companies, Tita-Kuru Petrochemicals Limited, had spent $40 million preparing for its actualisation.

But the 81-year-old billionaire retired army general was undercut by his consultant on the project who happened to be Michael “Mick” Quinn, the Irishman owner of P&ID.

“Quinn had been a consultant, using Danjuma’s funds and office space, the general said. When Quinn applied for the contract himself, Danjuma was upset,” Bloomberg Businessweek reports in its online edition of September 4, 2019.

The publication quoted Danjuma as saying that the reality dawned on him that, “my consultant was going to steal my project.”

Danjuma said he was promised a share of P&ID in return for his initial investment, but added that he had not heard from the company in years and that Cahill (Brendan Cahill), Quinn’s partner, hadn’t replied to letters about the P&ID’s lawsuit against the Federal Government of Nigeria.

“At one point, Danjuma dusted off his hands to emphasize the relationship’s end. P&ID’s spokesperson declined to comment on Danjuma’s involvement or any other matters raised in this story. Cahill didn’t respond to attempts to contact him directly,” the publication reported.

Bloomberg Businessweek hinged its report on the $9.6 billion judgment debt against Nigeria majorly on the account of one Neil Murray, said to be Michael Quinn’s close friend of 30 years.

An excerpt of the report titled: “Is One of the World’s Biggest Lawsuits Built on a Sham? A dying Irishman went for one last big score in Nigeria. The project failed, but a London tribunal says his company’s owed $9 billion and counting.”

The other case, of course, was P&ID. Nigeria’s desire to end flaring and provide power to the troubled Niger Delta had offered Quinn, almost 70 and in poor health, an opportunity to secure his legacy. “Mick was sick,” Murray said. “He wanted to go out on a big one.”

In 2012, once it had grown obvious the gas project wouldn’t come off, P&ID invoked its right to take Nigeria to arbitration in London. Three judges, two Brits and a Nigerian, oversaw the proceedings. From the start, Nigeria’s government seemed reluctant to participate. Its lawyers in Lagos didn’t provide a list of preliminary arguments until January 2014. Later that year, a few weeks before the first scheduled hearing, they told the tribunal they might not be able to set out the government’s case in writing or attend, “due to the inability of our client to provide us with complete instructions.”

P&ID’s submissions included a lengthy witness statement from Quinn, one of his last public declarations before he died. He described spending two years and an estimated $40 million on preparatory work for the gas plant, including a 3D digital model. “I cannot say with any certainty why the government failed to honour the GSPA,” Quinn wrote of the gas sale and purchase agreement. He suspected pressure from international oil companies was to blame. “In any event, I very much regret that we were prevented from implementing the GSPA, which I firmly believe would have been of significant benefit to the nation.” In outlining his history in Nigeria, he didn’t mention any of his military deals, the espionage charge, or the two other lawsuits against the country.

On the basis of largely unchallenged evidence provided by P&ID, the judges dismissed Nigeria’s objections and proceeded to the next stage: damages. According to the Abuja-based Premium Times, Quinn’s company agreed to settle for $850 million, but the government of President Muhammadu Buhari, who’d taken office in May 2015, rejected the deal. When the tribunal convened a hearing on the matter, Nigeria called only one witness—a lawyer who, in the words of the judges, didn’t “claim firsthand knowledge of any of the relevant events.” In January 2017 they awarded P&ID the profits they calculated it had missed out on because the plant wasn’t built: $6.6 billion, more than three times its original estimate of losses.

A ruling in London didn’t guarantee payment, though. P&ID’s lawyers took the judgment to several hedge funds that specialize in wringing cash from bad debts, according to someone familiar with the conversations. Records show they found at least one taker: VR Capital Group Ltd., a fund manager with offices in London, New York, and Moscow.

VR acquired one quarter of P&ID—which really meant, because the only thing of value P&ID possesses is a favourable legal ruling, that it was buying a share of the suit’s proceeds, presumably in return for helping finance the legal action. (Reached by phone, VR Capital President Richard Deitz said, “No. Can’t talk. I’m busy,” then hung up. The company didn’t respond to an emailed request for comment.) The remainder of P&ID is held by Cayman Islands-based Lismore Capital Ltd., whose ultimate owners are unknown. If the Nigerian government ever pays up, it will be impossible to know who benefits.

Last October law firm Kobre & Kim and public-relations specialist DCI Group registered with the U.S. Senate to lobby on behalf of P&ID. Op-eds critical of Nigeria soon appeared in Forbes and the Daily Telegraph, urging its government to honour the judgment; another, authored in London’s City A.M. newspaper by Priti Patel, a former British secretary of state for international development, accused the country of flouting international law. Journalists also began receiving messages from a group called P&ID Facts, whose emails list the same address as that of DCI Group. “The founders of P&ID have a track record of delivering in Nigeria and for Nigerians,” the organization’s website says. “The P&ID project was to be their swan song project after over three decades of public works projects in the country.”

Nigeria’s president thus far appears unmoved. A former general who styles himself as a simple cattle farmer and anticorruption crusader, Buhari has a relatively clean reputation. He responded angrily to Patel, issuing a statement through his spokesman that echoed what Pizzurro’s whistle blower had said: The P&ID lawsuit wasn’t what it appeared to be. “Before the coming of the Buhari administration, there existed in the country a racket encompassing elements in the three arms of government, the executive, legislature, and the judiciary through the activities of which artificial, engineered, and factored breaches of contract are made, judgments are obtained, appeals are delayed, and the penalty imposed is paid and shared,” the statement read. “Nigerians need to pity their own country for the way things were done in the past.”

A spokeswoman for P&ID said the panel of arbitrators had heard evidence from both sides and ruled unanimously that Nigeria failed to uphold its contractual commitments and was liable to P&ID. “It is unfortunate that instead of accepting the tribunal judgment and engaging in good-faith discussions to bring about a solution, President Buhari’s government has resorted to spreading unfounded allegations,” she said. She described the justice department’s corruption probe as a “sham” and said the government’s allegations were “entirely fictional,” adding, “The Nigerian people would be better served if the government made a serious offer to resolve this dispute rather than only blaming others, which will not make the legal obligation to pay go away.”

The list of Nigerians skeptical of P&ID’s position includes Danjuma, the 81-year-old billionaire and former general.